Every Land is a Holy Land: From Palestine to Turtle Island

by Brenna Cussen Anglada

Originally written in January 2024 for the Isidorian, a publication of the St. Isidore Catholic Worker Farm Community.

The remnants of our meal of hummus, falafel, pita, and yogurt remained on the restaurant table in the Old City of Jerusalem as my Israeli friend Chaim asked me to tell his friends why I had come to visit the Holy Land. It was 2004. Chaim and I had become close the previous year while studying International Peace at the University of Notre Dame, the same year that Israel had begun construction on what would become the 440-mile-long, 30-foot-high wall that now snakes in and around the West Bank, which, along with the blockaded Gaza Strip, has been under a decades-long occupation by Israel’s military. The wall has enabled the State of Israel to steal a significant amount of desirable land while cutting Palestinians off from their families, their livelihood, their olive groves, and their freedom.

It was an election year, and presidential candidates in the U.S. were deliberately obscuring the truth of this apartheid wall—paid for in large part by U.S. citizens’ tax dollars—by referring to it as a mere “separation barrier.” I told Chaim’s friends that I had traveled with fellow Catholic Workers in order to stand with the Palestinians and Israelis who were bravely, steadfastly, and nonviolently resisting the wall’s construction. In the journalistic spirit of Catholic Worker founder Dorothy Day, we would return home to write numerous articles and give dozens of talks about our experiences.

Chaim and his friends were Zionists, meaning that they believed in the right of Jewish people to establish, develop, and protect Israel as a Jewish-majority state in the land from which they had been exiled 2,000 years ago. (It is important to note that not all Jewish people are Zionists, and not all Zionists are Jews.) Zionism began as a political movement in the late 19th century in response to the long history of antisemitic policies and violent persecution from which Jews had suffered throughout Europe and elsewhere. As the full extent of the horrors of the Holocaust came to light, Zionism gained increasing support. In November 1947, the UN General Assembly partitioned Palestine—then under British rule—into one Jewish state and one Arab, with a shared capital of Jerusalem. The Arab world rejected the plan, arguing that it was unfair to give more than half of the land to a new State of Israel, while Arab Palestinians who had called this land home for centuries, and who until 1920 had made up 95% of the population, would be displaced.

During the war that followed Israel’s establishment, 750,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled from over 450 villages, many of which have since completely disappeared or been replaced by Israeli towns. (Read Blood Brothers by Bishop Elias Chacour for a personal narrative of this ethnic cleansing.) Today, the five million descendants of those Palestinians who fled remain scattered in a diaspora or live in refugee camps, unable to return to their homes. Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza continue to be displaced by Israeli military operations, Israeli settlements, land confiscation, evictions, and regular house demolitions.

Despite their Zionism, Chaim and his friends, devout Jews, disagreed with their government’s ongoing military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, and expressed respect for my faith-based commitment to justice and nonviolence. Still, they challenged me: “Why would you travel here to protest Israeli settlers’ theft of Palestinian land, when you yourself benefit from the ongoing theft of land from Indigenous people in your country?”

Their challenge struck a chord with me. My immigrant ancestors had accepted the myth promoted by European colonial powers that the U.S. had been “a vast wilderness,” ready for the taking. Those same colonial powers had insisted that Palestine before 1948 had been “a land without a people.” In both the U.S. and Israel, the new ruling power would use military violence to dispossess Indigenous people of their land. In both places, settlers continue to cooperate with the ruling power’s active attempt to destroy one culture and replace it with another.

Over the next few years, I returned to the West Bank several times to work with the Palestinian-led International Solidarity Movement, a nonviolent network that included Israelis and international supporters together resisting the Israeli military occupation. During my stays, I witnessed the daily horrors Palestinians experienced, including curfews imposed on entire villages that imprisoned families inside their homes without access to food or medical care for weeks, and the regular humiliation endured by Palestinians at military checkpoints that made travel to work or school always arduous, sometimes deadly. I saw Palestinian women and children getting patted down inside their own village of Tel Rumeida by Israeli soldiers while Israeli settlers and their visitors from the U.S. and Europe openly brandished automatic weapons on the streets. I looked on gratefully and helplessly as four Palestinian men carried my friend, a priest having a medical emergency, a half-mile to an ambulance, since Israeli settler-imposed road blocks had made travel impossible. I visited Palestinian families after Israeli settlers had attacked their olive groves and wells with poison in an attempt to drive them off their land. I joined weekly nonviolent protests, and witnessed leaders in the resistance movement face the fierce retaliation of the Israeli military: bullets, tear gas, sound grenades, midnight home raids by soldiers, and the kidnapping of children into Israeli prisons with no charges for months or years.

My last visit took place in 2009, a few months after the Israeli military had launched a three-week assault against the Gazan people, resulting in the deaths of 1,314 Palestinians. Israeli and Egyptian authorities had restricted food and medical supplies entering Gaza, a tiny area of 140 square miles completely sealed off from the world by the Israeli blockade. As the vast majority of Gaza's inhabitants were (and still are) imprisoned inside, hospitals had little access to medication.

I traveled with five other Catholic Workers, each carrying two large suitcases containing medical supplies and drawings sent by American children for Palestinian orphans. When we were denied entry into Gaza, we sent in our goods via an alternative route, and then traveled to Sderot, an Israeli town that had experienced the brunt of Hamas’ rocket fire. Nomika Zion, an Israeli citizen who had spearheaded weekly phone calls between Gazan and Israeli women, welcomed us. Nomika had recently written an op-ed in which she had chastised her government: “The bloodbath in Gaza is not in my name nor for my security.”

We then traveled to the West Bank village of Bil’in, where the villagers had been resisting the construction of the wall for years. The village was in mourning. The week before our visit, Bassem, a villager and beloved leader in the nonviolent movement, had been shot and killed by an Israeli soldier during the villagers’ weekly peaceful demonstration.

From Palestinians, I learned what it means to truly love the land. It was Palestinians who taught me what bravery and heroism looks like in the nonviolent struggle to protect the people and the places you love. Soon after my last visit, I moved to Dubuque, Iowa, to live and work on a Catholic Worker farm, in hopes that I, too, might fall in love with a place so deeply, and begin to know the land as intimately, as they.

And yet the challenge from Chaim and his friends continued to nag at me. I struggled knowing that my ability to live on this land was rooted in the forced removal and genocide of the people Indigenous to it. In 2015, my spouse Eric and I had a profoundly transformative encounter with Jim Bear Jacobs, a Stockbridge Munsee Mohican storyteller who has received permission from Dakota elders to tell the stories of both the genesis and the attempted genocide of the Dakota people in the place where they occurred. Learning from Jim Bear has led us for the last decade on a path of trying to repair some of the racial and ecological harm done through colonization on our own continent. This work has been deeply meaningful for both of us.

Over the last several months, my heart has been breaking as we have watched the genocide of the people in Gaza unfolding in real time. Following Hamas’ brutal attack on Israeli civilians, over 27,000 Gazan people have been massacred, and nearly two million displaced. In a terrifying statement in January, Israel’s Finance Minister suggested that Gazan residents abandon their homeland altogether, and let Israelis “make the desert bloom.” Israel is employing as methods of warfare both the illegal use of white phosphorus and the starvation of civilians. And the citizens of the U.S., through their tax dollars, are funding this genocide.

While my despair is deep, I find hope in the inspirational leadership of Jewish and Palestinian activists around the world who are speaking truth and taking action. The anti-Zionist organization Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) for example, has been steadfast in demanding a ceasefire - even organizing the shutdown of Grand Central Station as one of many direct actions. JVP continues to call for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions against entities supporting Israel's military occupation of Palestine.

The Christian response in the U.S. to the slaughter of our sisters and brothers in the Holy Land has been much more disappointing, however. Whether born from an active embrace of Islamophobia or from a deep guilt about our own role in the Holocaust and thus fear of saying the wrong thing - Christians for months have been either actively supporting Israel’s claims of “necessary defense” or have been silent. At his Christmas Eve liturgy, Rev. Dr. Munther Isaac, a Palestinian Christian theologian living in Bethlehem, called out the Western Christian world: “Let it be clear: Silence is complicity, and empty calls for peace without a ceasefire and end to occupation…are all under the banner of complicity.”

And yet recently, it appears that Christians have been waking up. On January 16, hundreds of Christians with Mennonite Action met in D.C. to demand an immediate ceasefire and an end to the US-funded occupation of Palestine. And on February 15, over 1500 Christians for a Free Palestine from across the U.S. gathered for a virtual mass call to learn how to similarly organize for an end to the violence. Join us on Monday, March 18, as we use our public voice and our collective power to advocate for peace, challenge Christian Zionism, and demand an immediate ceasefire.

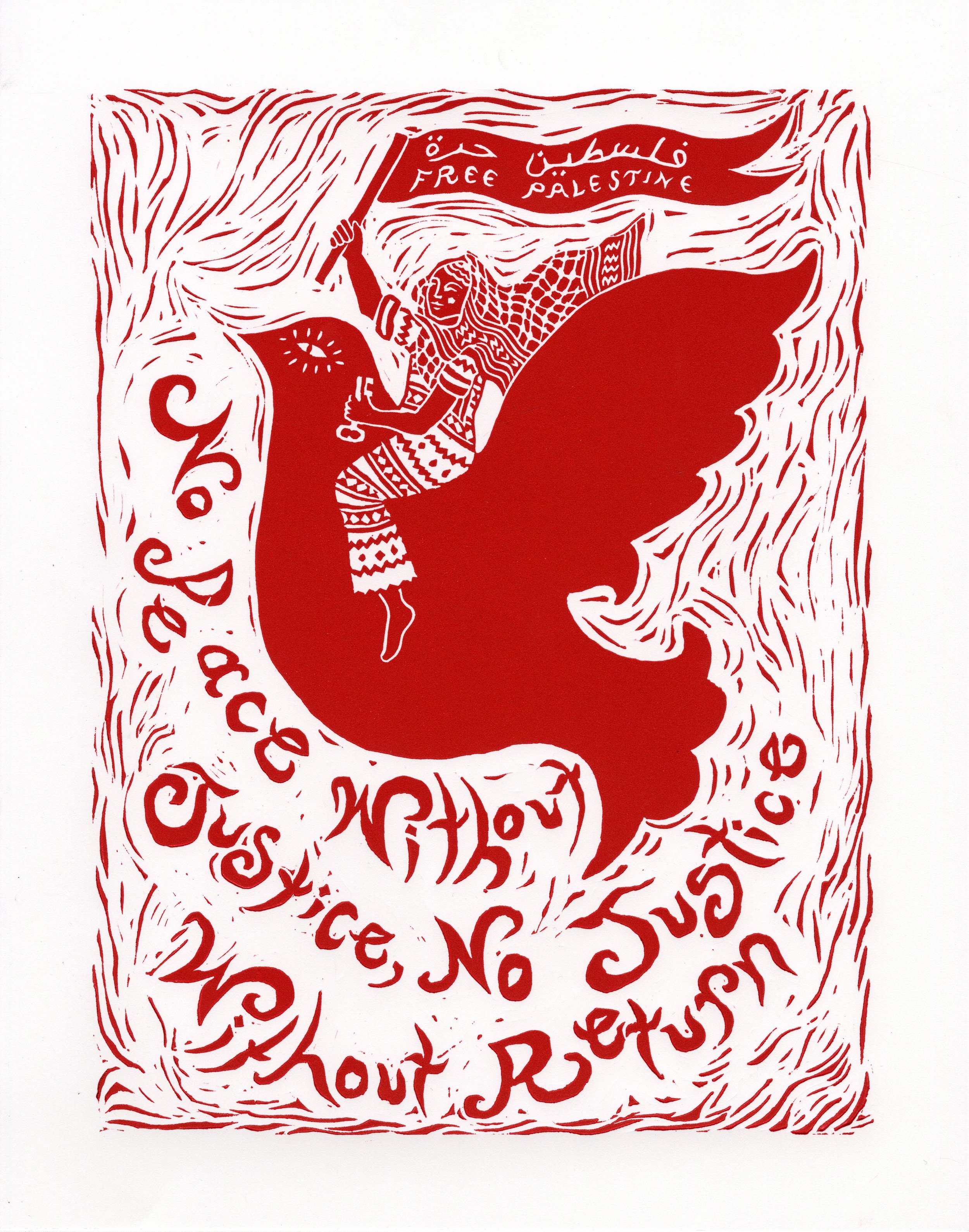

This image was made by Shanti Cordoni-Jordan (@shantiviolet on Instagram) and is a part of a free image collection about Palestine at justseeds.org.